OFFICIAL STATEMENT

The following report contains documented cases of police misconduct and systemic failures in accountability. All information has been verified through public records, court documents, and official sources. The Code of Silence remains committed to exposing the truth that powerful institutions would prefer remain hidden.

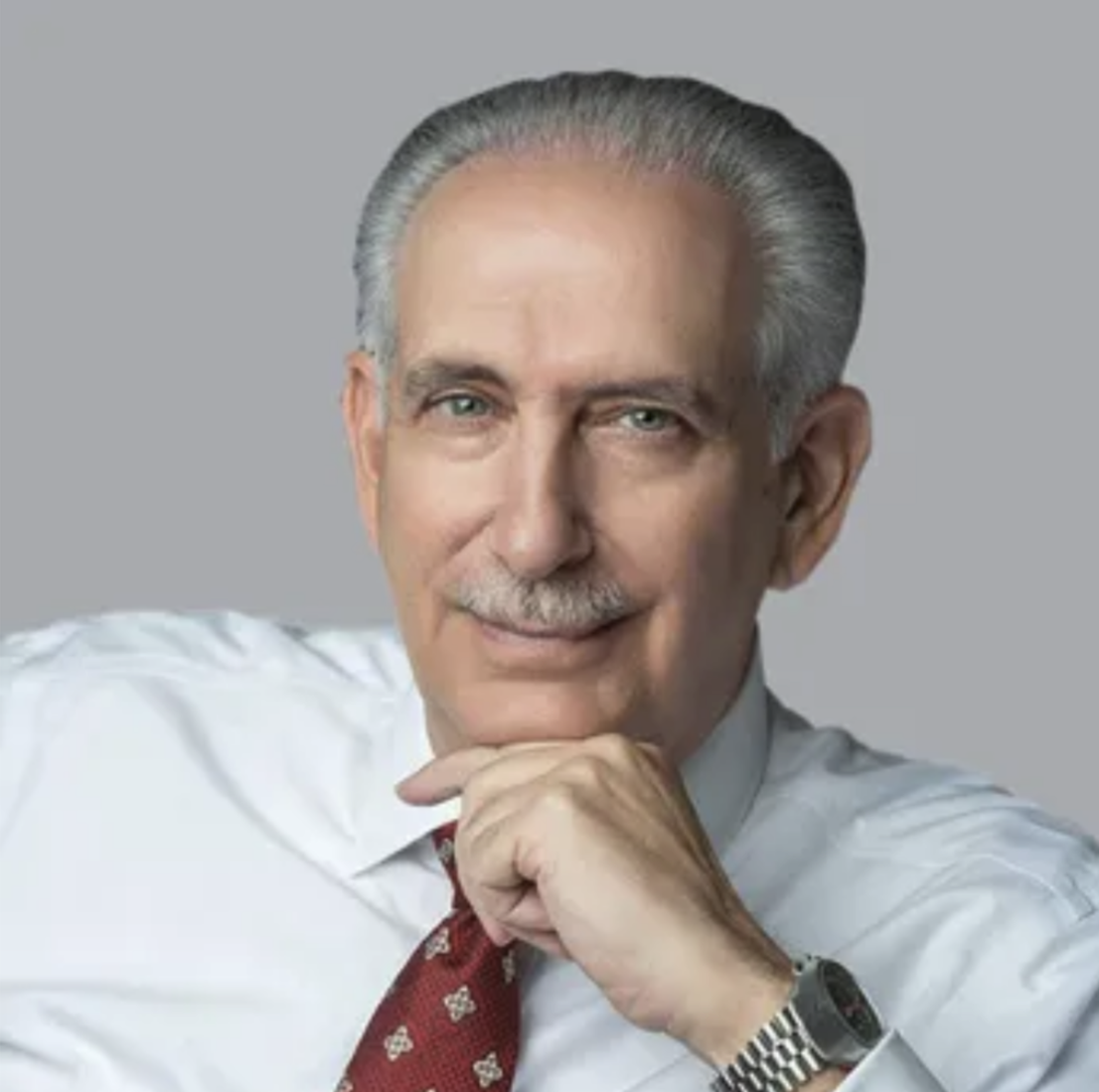

In February 2020, Westchester District Attorney Anthony Scarpino made public a list of police officers with credibility issues affecting their testimony in court cases. District attorneys across New York and elsewhere have reportedly maintained similar lists of officers who can't be trusted in court, and these lists are increasingly being released to the public.

Westchester DA Anthony Scarpino released a landmark report exposing credibility issues among local police officers in 2020.

But what about the officers who exploit the system of departmental transfers to escape scrutiny whenever there's a problem? The so-called "blue wall of silence" often halts internal investigations before they begin. Consider, for example, the case of Westchester County Police Academy graduate Jesus Bangurra.

Hired by the Pleasantville Police Department in 2019, Bangurra was accused by the father of a high school student of engaging in an inappropriate relationship with a minor at Pleasantville High School. When the father confronted him, Bangurra allegedly retaliated by attempting to charge the girl's uncle with DWI as a warning to the family.

Officer Jesus Bangurra, transferred from Pleasantville PD to Harrison PD amid disturbing allegations.

However, when it became clear that the father had connections of his own, Bangurra quickly submitted a transfer application to the Harrison Police Department. Harrison, eager to avoid training costs, accepted him with open arms—even boosting his Pleasantville \$102,103 salary in 2023 to \$120,776. Since then, new allegations have emerged involving Bangurra and another underage girl—along with continued reports of retaliatory DUI and DWI arrests. Harrison PD has claimed ignorance, pretending not to know about Bangurra's growing list of complaints.

Another disturbing case involves Michael Agovino of the Peekskill Police Department. Like Bangurra, Agovino targeted a female minor. But instead of issuing false arrests, he was caught breaking into the minor's home after her father warned him to stay away. Agovino's attempt to quietly transfer departments failed, and on June 23, 2022, he was sentenced to seven years in state prison for repeatedly sexually abusing a woman while on duty between 2019 and 2020.

Ex-Peekskill officer Michael Agovino, sentenced to seven years in prison for crimes committed on duty.

Then there's the case of Reinaldo Santamaria in Port Chester—a symbol of institutional cover-up. Instead of facing consequences, Santamaria was promoted to lieutenant, protected by a department riddled with scandal. In return, he enforced the blue wall of silence, helping the Port Chester Police Department bury misconduct, including his own inclusion on the Westchester County Brady list. The promotion made him virtually untouchable—a poster child for the failure of internal accountability.

Christian Gutierrez's story, another officer identified by DA Scarpino's report, starkly illustrates how the so-called "blue wall" selectively shields or abandons its members. In 2008, Gutierrez was involved in the tragic shooting of off-duty Mount Vernon Officer Christopher Ridley, a Black officer mistakenly gunned down by fellow officers. Despite public outrage, officers faced no charges. Nearly a decade later, Gutierrez made controversial remarks about Ridley during police training, leading county officials to shield him from consequences, prioritizing internal harmony over public trust.

"The system is designed to protect its own. When an officer gets in trouble, the first instinct isn't accountability—it's damage control. Transfer them, promote them, or help them retire quietly. The public rarely finds out the truth."

— Retired Westchester Police Sergeant (name withheld for protection)

Yonkers Mayor Mike Spano publicly condemning Officer Carrasco prior to due process.

In a striking example of political overreach, Yonkers Mayor Mike Spano quickly condemned Officer Christian Carrasco publicly, preempting judicial processes. This rush to judgment showcased political opportunism rather than genuine accountability.

Following Scarpino's release, police unions across Westchester, Rockland, and Putnam counties swiftly blocked FOIL requests, actively resisting transparency. In August 2024, the Westchester DA's office denied FOIL appeals for Brady list documents, claiming such lists don't exist while simultaneously acknowledging their compilation for internal use—a stark example of bureaucratic doublespeak.

As a retired police officer, I've seen firsthand how the system often shields misconduct. Officers like Peter Carracaterra, Leonard Cooper, Allan Fong, John Gamble, Bill Guzman, Orville Kitson, Kyle Kreuscher, Nehemiah Nelson, Jose Nieves, Jonathan Rubin, Steven Velasquez, and Joe Zepeda, each accused or convicted of serious offenses, typically retire or transfer quietly, escaping genuine accountability. For instance, Cooper remained employed after reckless driving; Fong's employment outcome was hidden; Guzman, convicted of DWI, retired comfortably; and Kitson faced multiple serious allegations yet resigned quietly. Kreuscher, convicted of DWI, remains on the force; Nelson's current role is unknown; Nieves continues policing despite a DWI; Rubin and Velasquez retired after serious offenses without significant consequence, while Zepeda remains employed despite a DWI conviction. It's disturbing evidence that even severe misconduct rarely derails police careers. Retirement or resignation provides a soft landing, perpetuating a cycle of unaccountability. It's crucial we question and dismantle these protections because, if we don't, who will?

What happens when that silence is no longer enough? What happens when a victim's family stops waiting for answers? Will Westchester County continue to protect officers who move from department to department like fugitives with a badge—never held accountable, never tracked, never exposed? Or will the wall finally crack, not from public pressure, but from within?

In Part 2, we follow the money, the politics, and the backroom favors that keep this broken system intact—and ask whether justice has already left the building.